A contributing factor to Republic First Bank’s failure is likely to stress more banks this year.

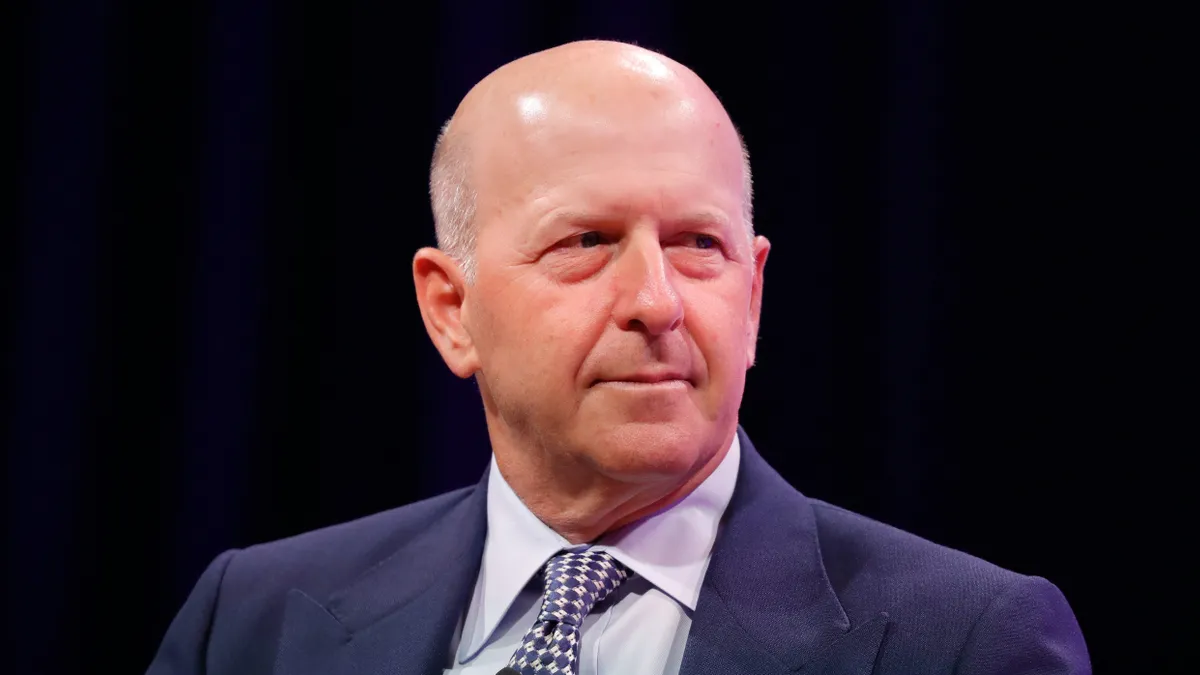

That’s according to Robert Hartheimer, a senior adviser at consulting firm Klaros Group. In the 1990s, Hartheimer served as the director of the division of resolutions at the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. and sold 200 banks during a four-year stint at the regulatory agency.

The year’s first bank failure came Friday, with Lancaster, Pennsylvania-based Fulton Bank agreeing to purchase substantially all of the assets of beleaguered Republic First and assume substantially all of its deposits. The Pennsylvania Department of Banking and Securities closed Republic First earlier in the day and appointed the FDIC as receiver.

Hartheimer said he expects more banks with significant unrealized losses, like Republic First, to face tough decisions this year, since higher interest rates have put pressure on the value of fixed-income securities. For other lenders, that may include weighing a capital raise or a sale, said Hartheimer, who spoke with Banking Dive on Monday.

Editor’s note: This interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

BANKING DIVE: How does a failed bank resolution scenario play out, based on your experience?

ROBERT HARTHEIMER: It seems like this was more of an orderly process. There’s staff at the FDIC that go in and take a look at the prospective failing bank’s balance sheet, and they essentially price both sides of the balance sheet and determine what can be sold. There’s always a preference to try and sell as much of the bank together, because it retains more franchise value and assists in making it easier on the community of the failed bank. If there was fraud or particularly ugly assets, the FDIC might take them out of what they’re offering for sale.

Then, essentially, a bid package is put together. They reach out to the supervision side of their agency and other agencies to determine who might be a qualified bank buyer, or private equity buyer, or shelf charter. Then, an M&A process commences. Calls are made: “We can’t tell you who the target is, but if you’ll sign a non-disclosure agreement, we’ll then provide you with information and a rough sense of our schedule.”

Prospective buyers take a look at what exists at the bank. The FDIC sets some dates, bids are submitted and analyzed, and there has to be back and forth. The FDIC has a regulation that they have to do the least-cost transaction, so they look at what it would cost them to liquidate the bank and pay out insured depositors, and then they compare, as a baseline, all the bids to that.

The winning bid was Fulton’s, and Fulton would have been notified once the FDIC board approved the transaction. Then, if it’s orderly, Friday at 3 o’clock, the FDIC dispatches people to branches and headquarters, the primary chartering agency comes in and pulls the charter, and it’s a sad day.

It’s not without emotion. This particular bank had some colorful management: CEO, former CEO, some activist investors. But at the end of the day, the failure really occurs with the rank-and-file and the people that manage the institution.

The buyer and the FDIC work through the weekend to get the technology in a place where the buyer can manage the acquired bank, and if everything goes right, it opens for business on Monday.

What’s the timeline like for such a process?

It all depends on the size and complexity of the failing bank. A faster, predictable process works for smaller, simpler banks.

What contributed to Republic First’s downfall?

This was a bank that did a lot of lending before interest rates went up, so there were embedded losses in certain assets, there were embedded losses in their liquidity portfolio. Besides loans, assets that are on a bank’s balance sheet, there’s a liquidity portfolio that all banks have to have, meaning they have to have a certain amount of very liquid assets on their balance sheet, as depositors come in and want their money. And under regulatory capital rules, if you have very high quality securities — like treasury securities — and those were bought at lower interest rate environments but they’re sitting on your balance sheet and you count them for capital, you don’t mark them to market, if they’re held to maturity.

This is what happened to Silicon Valley Bank, and there’s been a lot of lists of banks out there that have losses today, if the banks were to be liquidated, but for regulatory capital purposes, those losses don’t count. That has evolved into a problem, as interest rates have spiked in the last couple years.

That wasn’t the only problem with this bank. The cost of managing a bank, of managing compliance and risk, has all gone up. Put all that together, this is a bank that has struggled to do well. It’s rarely one thing.

So do you think we’ll see more banks in a similar position this year?

There are 4,000 banks out there. There will be banks that have similar problems to this, that will be working with their regulators and with advisers to try and put themselves out of these problems. So either by raising additional capital to ensure a real cushion, or selling themselves in a private-sector sale. There are others out there, of all different sizes.

If you have capital rules that allow you to count securities that have embedded losses but the losses don’t count, that’s kind of nerve-wracking, because the regulators are saying they’re well-capitalized but, in fact, on a mark-to-market basis, they’re really not well-capitalized.

Any criticism of past bank examinations after a failure like this occurs?

With every failure, there’s a post-mortem. The agency will look at the examination record over time, and what was told to the bank, and what the bank did or didn’t do. Whether examiners could have been a little stronger in seeking change, I don’t know. But the agencies involved here will want to learn from mistakes that were made, either by them or the bank.