The House Financial Services Committee last week passed a bill that would stop the Federal Reserve from working on a central bank digital currency, giving the full House a chance to consider the legislation.

The bill would amend the Federal Reserve Act to prohibit Federal Reserve-supervised banks from issuing “a central bank digital currency, or any digital asset that is substantially similar under any other name or label, directly to an individual,” according to the text of that proposed bill, H.R. 5403.

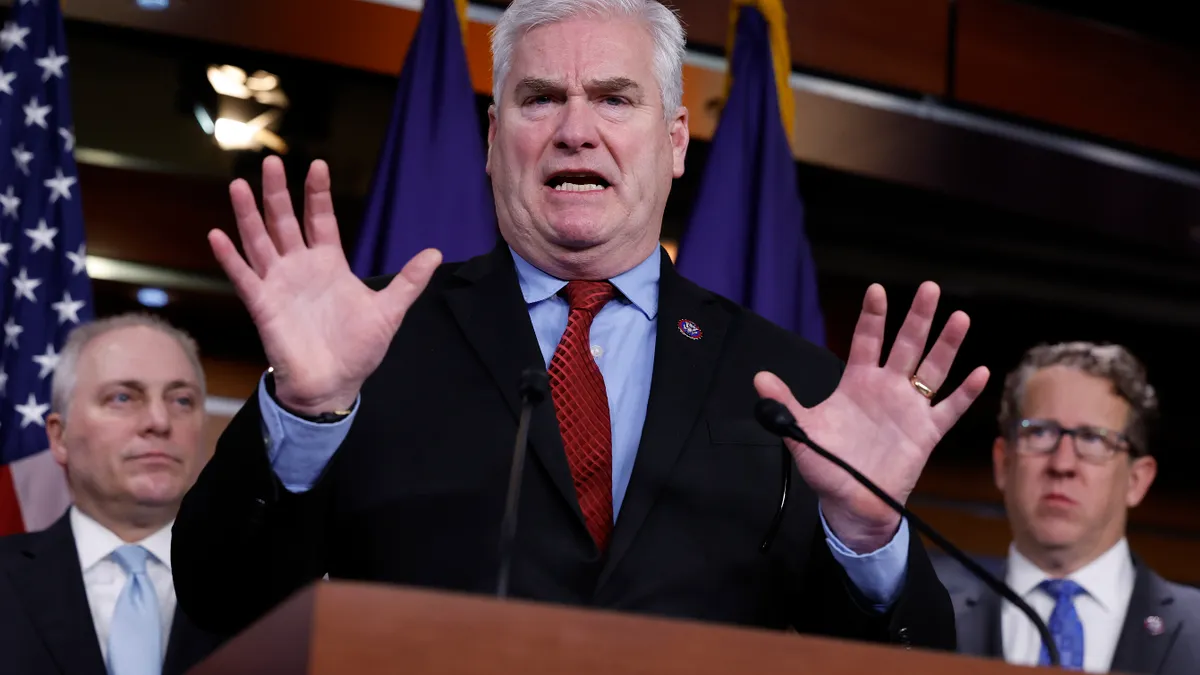

Rep. Tom Emmer, R-MN, who is also the House Majority Whip, proposed the bill, which he refers to as the “CBDC Anti-Surveillance State Act.” It was passed by the committee Wednesday to the House floor.

“This bill has the support of 60 Members of Congress and groups ranging from the Independent Community Bankers Association and American Bankers Association to Club for Growth, Heritage Action and the Blockchain Association,” Emmer said in a press release that day.

There doesn’t appear to be a Senate companion bill for the legislation at this time.

Earlier this month, at a hearing of the House Financial Services Subcommittee on Digital Assets, Financial Technology and Inclusion, Rep. French Hill, R-AR, who chairs the subcommittee, said he doesn’t see congressional support for a CBDC. Furthermore, he said House lawmakers on both sides of the aisle agree that the Federal Reserve wouldn’t have the authority to develop such a CBDC without an act of Congress.

Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell said as much himself in September 2021, as the Fed was working on a CBDC research paper that it released last year as a starting point for discussions. That paper defined a CBDC as “a digital liability of a central bank that is widely available to the general public.”

“There is no support for a CBDC in Congress, except from those on the fringes who think somehow a CBDC might be an amazing solution to many unstated global problems,” Hill said at the subcommittee hearing Sept. 14.

That doesn’t mean that Hill doesn’t believe the U.S. payments system is in need of improvements, he said. He noted that the Fed is overdue to expand the days and hours of Fed wholesale payment services like Fedwire and the national settlement service.

“It’s not OK that the Fed still hasn’t finished this work even a decade later with no clear timetable for its completion,” he said in his opening remarks for the subcommittee hearing.

Lawmakers heard from representatives of Washington think tanks, universities and a digital asset company at the subcommittee hearing earlier this month.

Congressional opposition to a CBDC

Hill said he’s concerned a CBDC might empower the Fed to monitor users’ transactions, and thereby infringe on their rights to privacy.

“Payment and transaction data can tell you a lot about somebody,” Hill said.

Rep. Mike Flood, R-NE, echoed those concerns, saying he opposes a retail CBDC because it allows for the “concentration of power in the hands of the federal government.” He contended it could give the federal government the ability to block certain people from using the currency, or block users from making certain purchases.

Rep. Sean Casten, D-IL, who noted the subcommittee has been reviewing the CBDC issue for two years, said he sees no benefit to such a currency over the current U.S. currency, despite other countries pursuing this type of digital alternative.

One witness testifying before the subcommittee offered a contrasting view. “My opinion is that it is incumbent upon the United States to provide leadership with respect to an inevitable process that is going to occur across the world,” said Raúl Carrillo, a professor at Columbia Law School. “It is clear that we are all moving to digital fiat currency. The question is what sort of digital protections are going to attend digital fiat currency.”

Allowing technology companies in Silicon Valley to dominate the creation of such digital currencies isn’t advisable, Carrillo argued. He backs legislation proposed earlier this month by Rep. Stephen Lynch, D-MA, to create a different version of a digital dollar — one that doesn’t operate on a blockchain and preserves users’ privacy, he said.

Popular private cryptocurrencies, such as Bitcoin, often operate on blockchain technology that allows users to jointly monitor the digital assets.

Lynch’s digital dollar legislation

Lynch, who also sits on the subcommittee, gave a plug for his bill during the hearing, as he urged members to consider the various forms a digital currency issued by the U.S. could take. He also noted some 130 countries are exploring CBDCs. “Meanwhile, the U.S. remains far behind,” he said.

Lynch shares CBDC concerns related to privacy and government surveillance, but a digital currency, like the one he’s proposed, could be designed to avoid those threats, he said. He stressed that financial services companies are already using digital payments to pry into consumers’ personal data.

His bill proposes an Electronic Currency and Secure Hardware (ECASH) Act that would require the Treasury to create a digital dollar version of cash that would complement a Fed CBDC, he said. That digital dollar would allow for instant peer-to-peer payments without data tracking and without using a bank account, he said.

“I hope my colleagues will join me in this exploration, rather than moving legislation that bans the Fed from issuing a CBDC,” he said.