Goldman Sachs on Monday laid out a raft of bolstered employee benefits in perhaps its latest bid to soften a hard-charging image.

The bank is increasing — to 6% — the amount it’s willing to match in U.S. employees’ retirement fund contributions, it said in a memo seen by The Wall Street Journal and Bloomberg. That’s a two-percentage-point bump, according to the latter. Further, that proportion jumps to 8% for employees making $125,000 or less per year. In another policy change, employees will no longer have to wait a year before the bank begins matching those contributions.

But that’s money. Goldman Sachs is arguably good at money. The bank amassed more revenue over the first nine months of 2021 than it had in any previous 12-month period.

Goldman is comfortable seeing the world through a money lens. Comfortable enough that its consumer bank, Marcus, uses "money" as a verb in its tag line.

Soft skills, on the other hand, may be a growth area for the bank’s image. And here, Monday’s policy changes take a compelling turn. Goldman employees will be eligible for 20 days of paid leave if they, a spouse or a surrogate have a miscarriage or stillbirth. The bank is also expanding its paid bereavement leave to 20 days for the loss of an immediate family member and five days for the loss of a non-immediate family member.

Goldman is also offering a six-week unpaid sabbatical to employees who have been at the bank for 15 years or more.

Two satisfaction pillars

When assessing satisfaction, employees typically seek to change one of two pillars: money or time. Goldman’s attitude toward both has come under fire this year — to varying degrees. Sometimes in the same narrative.

When a group of 13 Goldman junior analysts in March presented to their managers a self-survey detailing "inhumane" 100-hour workweeks, deteriorating physical and mental health and a souring outlook for the future, splashy headlines emphasized the time aspect.

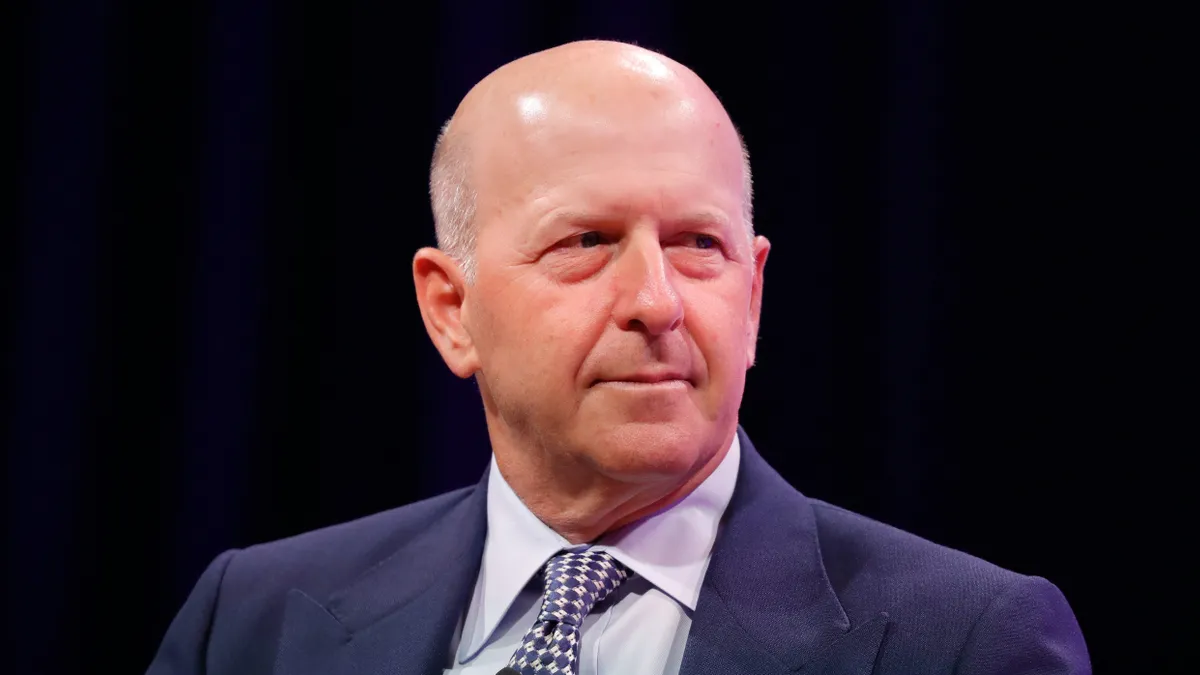

And time was indeed the first concern CEO David Solomon addressed in a voice memo after news of the self-survey went viral. "In this world of remote work, it feels like we have to be connected 24/7," Solomon said. "All of us — your colleagues, your managers, our divisional leaders — we see that."

Solomon, in the memo, told employees the bank would strengthen enforcement of its Saturday rule, which mandates that analysts be out of the office from 9 p.m. Friday to 9 a.m. Sunday.

However comforting, that was less a new policy than clamping down on an old one.

The victory for junior analysts — arguably across the banking industry — came on the money side, without heed to time.

Bank of America, Wells Fargo, JPMorgan Chase, Citi, Barclays, Deutsche Bank and Morgan Stanley began offering heftier salaries to junior investment bankers, and attention turned to how Goldman would respond — in a "dollars" sense. It took a while: The bank didn’t stray from its usual timeline to offer compensation boosts. But Goldman bumped its starting compensation to $110,000 — the front of the line among the six largest U.S. banks. (Morgan Stanley later matched that benchmark.)

Seizing the narrative

Monday’s new benefits policy allows Goldman to up its game on the time side. Messaging connected to the rollout appeared to alternately focus on time and money.

"We wanted to offer a compelling value proposition to current and prospective employees, and wanted to make sure we’re leading, not just competing," Bentley de Beyer, Goldman’s human resources chief, told The Wall Street Journal.

That message tracks with Goldman’s junior analyst salary strategy. However, a second comment stressed the bank’s commitment to employees’ time.

"We’re focused on delivering energy optimization, resilience and mental-health programs that support our people in caring for themselves and their families," de Beyer told Bloomberg in an emailed statement.

The challenge may be getting employees to buy into the cultural shift — and for management to follow through on it.

A May survey by the Bipartisan Policy Center and Morning Consult found paid family leave to be used at high rates among employees who were offered it. But only 28% of workers had that option.

Goldman instituted paid family leave for employees facing COVID-19-related issues last year. As for other leave, employees may have to be convinced they won’t be stigmatized for taking it.

"Taking a sabbatical is not the kind of thing that super-engaged executives do," Peter Cappelli, the Wharton School’s director of the Center for Human Resources, told The Wall Street Journal.

Goldman wouldn’t be breaking ground here. Citi — a bank better known for its employee-friendliness — announced a policy last December under which employees who have been with the bank for at least five years can take a sabbatical of up to 12 weeks and get 25% of their base pay during their time away.

Unlike Citi, which in March said most employees could adopt a hybrid schedule including at least two remote days a week after the COVID-19 pandemic subsides, Goldman earned its reputation as a hard charger. Solomon in February called the bank’s remote-work era an "aberration," and the bank asked U.S. employees to prepare to go back to the office in June. That month, Goldman became the first of the six largest U.S. banks to require workers to report their vaccination status.

As for Goldman’s opportunities to trumpet its contribution to the common good, the bank has been relatively effective when the benefit is monetary and measurable. Goldman was among the first big U.S. banks to make a sizable commitment to environmentally conscious financing — and to document its progress a year into the effort. But again, that’s money.

On time-focused social issues, such as a Juneteenth policy, Goldman has been the least vocal of the U.S.’s six largest banks.

Perhaps a culture change — and its accompanying perception — just needs the right launchpad.