Banks that took part in the Federal Reserve’s climate scenario analysis reported “significant” challenges with data and modeling as they sought to estimate climate-related financial risks.

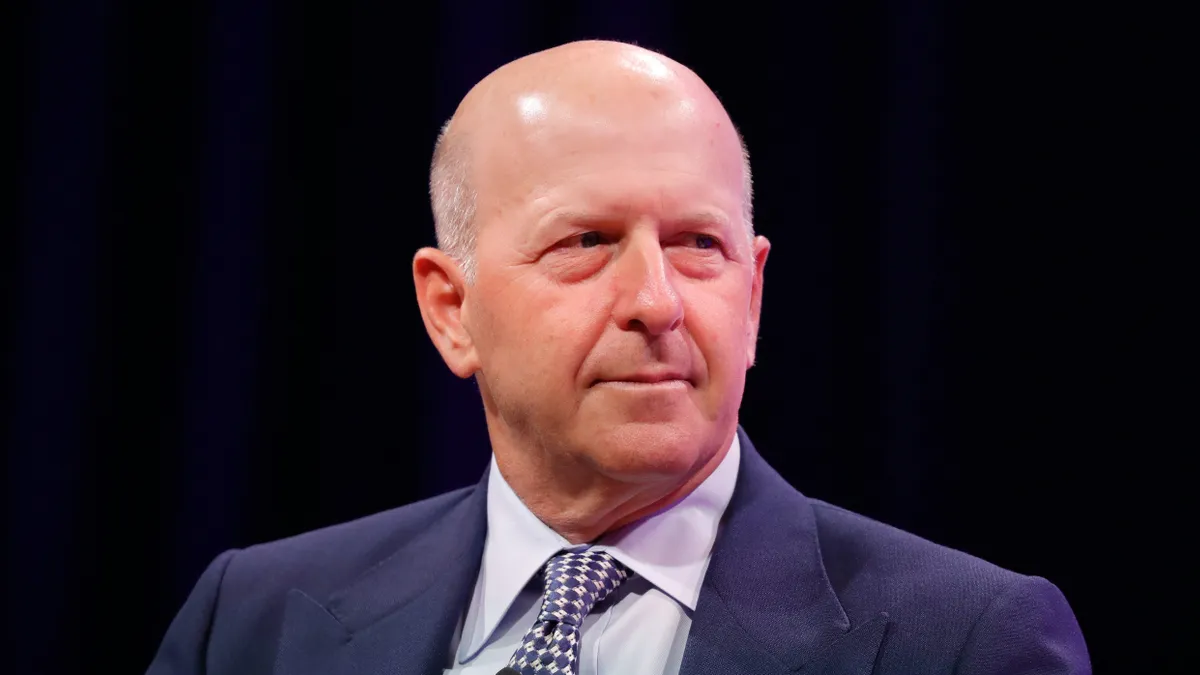

That’s among the takeaways from the months-long exercise the central bank conducted last year with the U.S.’s six largest banks, according to the report the Fed released Thursday. JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America, Citi, Wells Fargo, Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley took part in the exercise, which the Fed said didn’t have any consequences for bank capital or supervisory implications.

The exercise, announced in 2022, was “exploratory in nature,” the Fed said, and meant to serve as a snapshot of the biggest banks’ climate risk-management practices and challenges, and also to bolster the ability of large banks and supervisors to spot, estimate and manage climate-related financial risks.

Ultimately, the exercise revealed climate change and the shift to carbon-free or renewable energy sources could yield a rise in loan defaults for the nation’s biggest banks.

As they went through the exercise, the lenders encountered particular hurdles related to data — finding data gaps related to real estate exposure, insurance, debtors’ transition risk management and infrastructure, the Fed said.

“Participants suggested that climate-related risks are highly uncertain and challenging to measure,” according to the report. “The uncertainty around the timing and magnitude of climate-related risks made it difficult for participants to determine how best to incorporate these risks into their risk management frameworks on a business-as-usual basis.”

As part of the exercise, banks were asked to detail impacts to their residential and commercial real estate lending portfolios based on two scenarios: one in which a severe hurricane affects the Northeast, since each bank has substantial investment in the region; and a second in which a natural disaster of their choosing hits another region of the country relevant to their real estate portfolios.

In the “most severe” scenario — a 200-year period where no properties are insured — more than 1,000 commercial real estate loans and more than 238,000 residential real estate loans in the Northeast were affected, representing about 20% and 50% of participants’ total commercial and residential real estate loan counts in that region, respectively, the report said.

Participating banks were also asked to assess impacts of transition risk, which refers to business-related risks tied to the shift to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and move toward renewable energy, according to the Environmental Protection Agency. The Fed’s report revealed insights gained from the pilot at an aggregate level; it did not contain firm-specific information.

With Citi’s $730 billion in wholesale loans assessed as the bank’s part of the Fed study, Reuters last week published a report based on a draft of Citi’s contribution to the exercise, which said the bank would suffer $10.3 billion in loan losses over a decade if the effort to fight climate change accelerated enough to put the world in line for net zero by 2050.

If climate change-fighting efforts didn’t ramp up, however, the bank would lose $7.1 billion over 10 years, Reuters reported. That lines up with the Fed report’s note that participating banks projected the probability of default was higher in a net zero 2050 scenario for corporate and CRE loans, with average default probability about 30 basis points higher for corporate loans, and about 100 basis points higher for CRE loans.

Banks took varying approaches to crafting detailed risk scenarios used in the pilot, and estimating climate-adjusted credit risk parameters, the Fed said, adding that banks’ various business models, views on risk and access to data influenced their approaches. Whether banks had participated in climate exercises in other regions of the world also shaped their approaches. Many had already done so, the Fed noted.

To address data challenges, banks told the Fed they plan to further invest to better map out climate-related financial risks, seeking more granular data and bolstering their modeling capabilities. Banks also aim to shift from third-party vendor models to in-house solutions, the Fed reported.

“Drawing on lessons learned from the exercise, the Board will continue to engage with participating banks regarding their capacity to measure and manage climate-related financial risks,” the Fed said in a news release Thursday.

Although the findings of the report weren’t necessarily surprising, they did point to the need for more collaboration among federal, state and local entities, to ensure banks have relevant information, said Peter Dugas, executive director of consulting firm Capco.

“I don’t necessarily think that was the intended outcome, but there were several instances where you can clearly see that banks would need to better collaborate with local governments as well as regional governments to be able to better understand things like building codes, land use issues, and really coming up with a process or procedures in order to collect and monitor that information,” Dugas said.

Dugas said he expects the Biden administration will determine that federal agencies such as the Treasury, Commerce, Housing and Urban Development departments, the EPA and the Federal Emergency Management Agency, need to collaborate with industry to better understand how they might assist with this endeavor. Working with building trade groups and insurance companies could benefit the process, too, Dugas said.