Aspiration Bank is a neobank founded on the premise that some customers want to "align their money with their morals," CEO and co-founder Andrei Cherny said.

Those customers not only want to know what their bank is doing with their deposits, but they want to see those deposits put toward social and environmental causes, he said.

But what happens when a pandemic disrupts the economy, forcing many to pay closer attention to their wallets amid uncertainty? Aspiration Bank allows customers to round up to the nearest dollar to help support the planet, but does that quality become less attractive when consumers are pinching their pennies?

Not in the least, Cherny told Banking Dive.

"What we’ve seen during the COVID-19 crisis is that our customers want to do more, not less, to take action to save our planet," said Cherny, who co-founded the challenger bank in 2013.

Aspiration, which has more than 1.7 million users, launched its latest initiative, Plant Your Change, in mid-April, a feature that allows debit card customers to round up purchases to the nearest dollar. Funds are then used to plant trees.

Cherny said the initiative has received a strong response — the company says 1 million trees have been planted since the initiative’s launch amid the coronavirus pandemic. Cherny would not share the total amount Aspiration customers have contributed, but said the average roundup is less than 50 cents.

"We wondered whether this was the right time to launch something like this," Cherny said. "Was it the right time to ask people to give up more of their spare change with every one of their purchases given the kinds of challenges that we're facing as a country?"

But Cherny said the country’s slow response to the coronavirus is not unlike its handling of climate change.

"We decided it was the right time because a big part of why we as a country are in the midst of this crisis is because we didn't act boldly enough and quickly enough when we could have to respond to COVID," he said. "We're long past the point of responding quickly [to climate change], but we still have time to respond boldly, and in a big way and for each individual to step up."

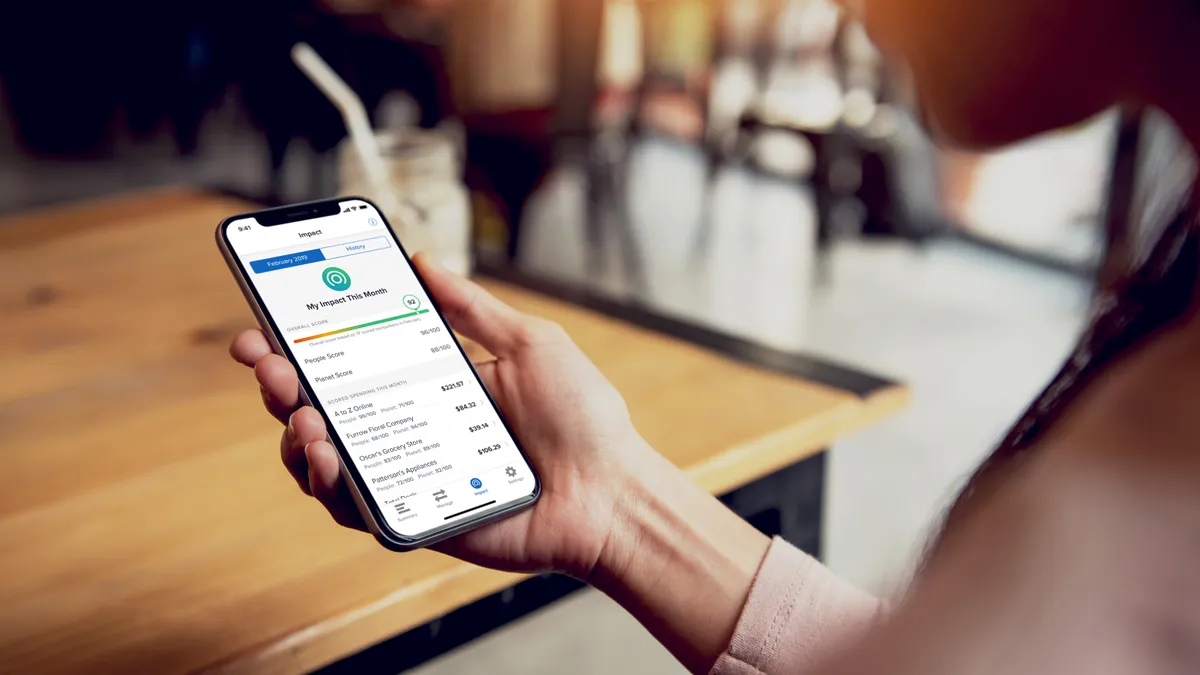

Aspiration’s products include other environmentally-minded features, including the ability for customers to view their personal sustainability score and the score of the places they shop.

The Los Angeles-based bank allows customers to make their personal car use carbon-neutral with an automatic carbon offset for all their gas purchases. It also promises customers their deposits are fossil fuel-free and never used for oil and gas exploration or to build pipelines.

Cherny said he thinks it will take "a force of competitive pressure" from institutions like Aspiration to get the nation’s largest banks to pursue similar sustainable initiatives.

"[Big banks] make so much money lending to big oil companies, due to pipelines like the Dakota Access Pipeline or Keystone Pipeline," he said.

Big banks’ connections to fossil fuels and oil and gas projects have come under fire from some environmental groups recently, and banks such as Citi and Wells Fargo have announced plans to invest in renewable energy or scale back ties to fossil fuels.

Wells, JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America and Goldman Sachs are financially backing a clean energy nonprofit's Center for Climate-Aligned Finance. The Rocky Mountain Institute last week launched the effort, which aims to collaborate with banks to design guidance for working with carbon-heavy sectors such as steel or utilities, and to help banks determine which climate benchmarks and data to follow.

Revenue often drives when banks enter or leave a sector. A February study by management consulting firm Oliver Wyman found climate change-related policy shifts, such as a carbon tax, could cost the financial industry up to $1 trillion.

But for Aspiration, whose celebrity investors include Leonardo DiCaprio and Orlando Bloom, the motivation to provide environmentally responsible banking services to the general public has been present from the start.

"A lot of customers who are sitting at these big banks don't know that there's an alternative that is more in line with what they're looking for in their own life," he said. "And sometimes they don't even know the intersection between where their deposits are sitting and the impact of those deposits.

"We're excited about what we've created thus far, but we also know that we’ve just scratched the surface of what's possible," Cherny said.